History

History

The Dark Lady of DNA

Rosalind Franklin made critical contributions to the discovery of DNA's structure, yet was not awarded the Nobel. Why not? Rank villainy? Maddox's masterful recounting lays out the complex tale.

fin de siècle German optimism

This is the first history of Germany I have read since the mid-1970's. It is nearly a complete history, stopping in 1883, ten years after it's author died. (his wife extended the history 14 more years in a subsequent edition.) An American writer, Bayard Taylor was most well-known for his travel writing, but was also a poet and a historian. His history reads easily, as might be expected from a writer of popular travel accounts, and is reasonably complete.

The smartest Nazi

Albert Speer, Hitler's personal architect and Reich Armaments Minister, kept a diary while he was in Spandau prison following his conviction at the post-war Nuremburg trials. These diaries provide a fascinating, hooded glimpse of the 'smartest man' in the Nazi leadership. At least, smart enough to evade the death penalty at the Nuremberg Trials.

Napoleon

Napoleon: A Life, by Andrew Roberts. My early view of Napoleon was as a cartoon figure: A megalomaniac who tried to take over the world. I recall looking down at Napoleon's tomb in Paris in the company of my brother Craig, the two of us mocking his immense sarcophagus and elaborate surroundings, wondering aloud why the French would semi-deify such a bloody tyrant. The typical American republican conceits aside, we were woefully uninformed about much of the life of Napoleon.

Napoleon: A Life, by Andrew Roberts. My early view of Napoleon was as a cartoon figure: A megalomaniac who tried to take over the world. I recall looking down at Napoleon's tomb in Paris in the company of my brother Craig, the two of us mocking his immense sarcophagus and elaborate surroundings, wondering aloud why the French would semi-deify such a bloody tyrant. The typical American republican conceits aside, we were woefully uninformed about much of the life of Napoleon. Trent: Too little, too late

Trent: What Happened at the Council, is a well-researched and well-told history of the Council of Trent, the mid-sixteenth-century Counter-Reformation centerpiece which produced the Catholic Church's response to the Protestant Reformation. This acount is carefully grounded in the complex politics of its times, placing the history of the Council in the balance- of-power tug-of-war, not just between reform movements within and without (Protestants) the Church, but among the nascent Ottoman Empire, the English Reformation, the Holy Roman Empire, the Papal States and the French monarchy.

The physical sublety of life

I recently re-read portions Erwin Schroedinger's amazing little book What is Life?, which was a post-war stimulus for a number of physicists to switch from physics to biology and look hard for a physical understanding of living organisms.

Why read history?

Adam Gopnik recently asked: Does it help to know history? Here is the first part of his answer:The best argument for reading history is not that it will show us the right thing to do in one case or the other, but rather that it will show us why even doing the right thing rarely works out. The advantage of having a historical sense is not that it will lead you to some quarry of instructions, the way that Superman can regularly return to the Fortress of Solitude to get instructions from his dad, but that it will teach you that no such crystal cave exists. What history generally “teaches” is how hard it is for anyone to control it, including the people who think they’re making it.

The full essay can be found here.

The Origins of Modern Science

Herbert Butterfield, in his book The Origins of Modern Science, tells the story of the development of modern science by focusing on the ideational changes in what is now referred to as science from the late Middle Ages until the advent of the French Revolution, with primary emphasis on the development of the modern understanding of motion. This is a brilliant choice, as it was the development of a robust physical and mathematical model of motion that allowed Newton to unite terrestrial and astronomical physics into a universal set of physical laws describing mechanics.

The origins of modern society

Ernst Troeltsch was a fin de siècle Protestant theologian who wrote Protestantism and Progress: A Historical Study of Protestantism and the Modern World. This work, along with his friend Max Weber's The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, both written just before World War I, are reasoned historical treatments of the influence of Protestantism on the perceived and potential progress of Western society. They provide effective contrast to the often simplistic and one-sided efforts by Protestant Evangelicals to do the same, such as Francis Schaeffer's How Should We Then Live?

Convivencia is a state of mind

Geraldine Brook's historical novel, People of the Book, tells the fascinating and uplifting story of how people of different faiths created and protected a Jewish book of worship known as the Sarajevo Haggadah for over five hundred years, a period marked by much religious conflict.

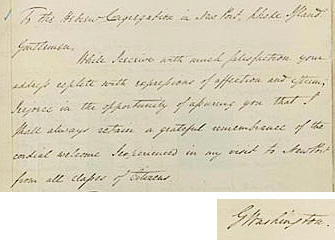

To the Hebrew congregation in Newport Rhode Island

A remarkable and short exchange of letters between George Washington and Moses Seixas in 1790 beautifully illuminates the Constitution's 1st Amendment protections for religious freedom as intended by the founders, written as the states were still ratifying the proposed Bill of Rights.I, Benvenuto Cellini

Benvenuto Cellini was a master Florentine goldsmith and sculptor who lived and worked during the time of the High Italian Renaissance, and was also, by his lights, tougher and craftier than anyone around him, could take on many men with a sword and live to tell the tale, was a great lover, and so on. His is the most ebullient autobiography I have read, and so wonderful, and so full of life!

Humbled again by particle physics

This is a history of the development of the Standard Model of particle physics, circa 1986. It is well regarded by physicists for its sociological treatment, as well as its attempt to record the false starts and uncertainty that accompany leading edge science; certainly the personalities and their various collaborations and squabbles are vividly rendered. As to the science, it is particularly good in providing a pithy description of how a unified theory of electromagnetic, strong and weak forces gives rise to our description of the early events of the Big Bang theory.

The ghost of Schaeffer past

By the time Charles Colson got out of prison in the mid-70's, having been convicted for acts of political skullduggery during the Watergate scandal, he had converted to Evangelical Christianity. How Now Shall We Live was his best-seller, an homage to Francis Schaeffer's view of Western history. Schaeffer was a presuppositional millennialist who in the 1970's left the quiet life of a Christian intellectual to help lead the evangelicals to the heights of political activism we see today in the U.S.

Voltaire is a sharp kick in the pants

Voltaire always had his wits about him. When once a visitor arrived, announcing that he had just come from a visit to another well-known writer, Voltaire offered the opinion that the aforementioned writer was a man of talent, and the visitor replied that that writer did not hold the same opinion of Voltaire, to which Voltaire retorted, 'We could both be wrong.'

Nothing is something

"Diddly squat is as close to squat as makes no nevermind." (page 124)

This is a superb and far-ranging essay on the apparently mundane zero. While it might be expected to be predominantly mathematical, it is much more, an erudite and masterly exposition that touches many disciplines without slighting its mathematical roots. It has an exponential arc.

This is a superb and far-ranging essay on the apparently mundane zero. While it might be expected to be predominantly mathematical, it is much more, an erudite and masterly exposition that touches many disciplines without slighting its mathematical roots. It has an exponential arc.Jefferson’s legacy

Joseph Ellis provides us with an ambitious analysis of the compartmentalized mind of Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson was extraordinarily adept at saying and writing, apparently believing, and doing things that were paradoxical and often diametrically opposed to each other. Ellis suggests that this helps to explain his enduring following by just about every political persuasion in the United States, and even abroad: Anyone can find in Jefferson something that supports one's ideology, especially if they studiously ignore, in perfect Jeffersonian fashion, the things Jefferson said or did that would negate their ideology.

Reasoning with Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine was perhaps the most persuasive of those proponents of revolution in the American Colonies of Great Britain, and well after his influential pamphlet Common Sense he continued to write about 'revolting' things (tongue well in cheek) in the following period of the French Revolution. His pamphlet Age of Reason is a fiercely argued defense of freedom of religion, an argument against organized religion and an argument for deism, written between 1794 and 1797 from Revolutionary France.

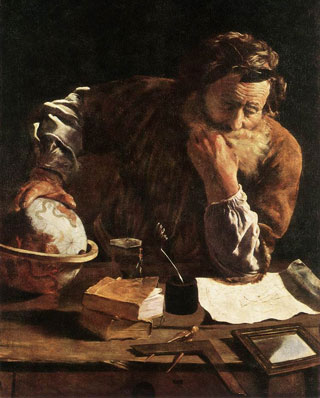

Sleepwalking amid new ideas

Arthur Koestler's book Sleepwalkers: A History of Man's Changing Vision of the Universe is an ambitious attempt to describe the development of Western cosmology and astronomy from the Greeks to Newton, with particular focus on Copernicus, Brahe, Kepler, and Galileo. Koestler did not see science as a linear and unbroken line of rational progression; instead he viewed the course of the history of ideas as somnambulant: Many ideas were stumbled upon by men with goals and mindsets alien to the very ideas they uncovered.

Slavery was the First Cause of the Civil War

It has always been for me somewhat of a puzzle as to why many in the South up to today insist on the idea that slavery was not a primary cause of our Civil War, but that states rights, economic warfare, etc. or anything but slavery were the deep and the proximate cause of that war. Charles Dew, born and raised in the South, writes this monograph on that very subject. He comes at the subject by researching the various documents created and speeches made by the politicians and government officials of Southern states prior to the start of the Civil War for the purpose of justifying, insisting upon, and finally enacting the secession of the various states from the Union.

Is religious tolerance religious freedom?

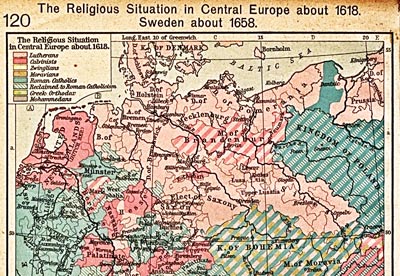

The ensuing religious fragmentation of Western Christendom following the advent of the Reformation created fissures in the fabric of European society so large that, after a century of warfare, borne by the exhaustion of bitter hatred and its accompanying destructiveness, the only option left for a more peaceful existence was the grudging co-existence of groups with religious differences.

The ensuing religious fragmentation of Western Christendom following the advent of the Reformation created fissures in the fabric of European society so large that, after a century of warfare, borne by the exhaustion of bitter hatred and its accompanying destructiveness, the only option left for a more peaceful existence was the grudging co-existence of groups with religious differences. Swerving into modernity

Stephen Greenblatt's book The Swerve: How the World Became Modern is an excellent tale of the influence of Epicurus on the modern way of thinking. Epicurus spoke of change in terms of a 'swerve'; the author's allusion to a swerve otherwise is to the narrow and chance survival during the Renaissance of Lucretius' poem De Rerum Natura, a rumination and celebration of all things Epicurean, and whose influence in subsequent Western thought represents a giant swerve in cosmology, religion and natural philosophy away from Plato and Aristotle and towards Epicurus.

The Genius of Apple

Steve Jobs recent demise brought out many encomiums having at least one thing in common: An agreement that he was a genius. Jobs' genius (a notoriously fickle word) would appear to be in the realm of practical design. His early Apple computer was easier to use and more accessible to its consumers than those of his early competitors, and that was true of most of the subsequent devices produced by Apple on his watch, including the Macintosh windowing and mouse-driven operating system, the seductively simple iPod, the iPhone marriage of mobile phones with a personal digital assistant and its deft employment of touch screen technology, and the iPad tablet offshoot.

Oregon loves New York: memories of 9/11

My wife Cindy and I awoke early on September 11, 2001 in Portland, Oregon. As I was preparing for work, she called me to the television, which had the smoking image of the first of the burning World Trade towers. We both stared in disbelief, and watched numbly as that terrible day unfolded, as the second tower was struck, as people began to jump from the buildings, after which one building and then the other crashed to the ground, so rapidly as to seem completely unreal. We watched as the Pentagon was struck, and followed the tense and fragmentary reporting as planes were grounded, fighter planes were scrambled, and frantic searches were being conducted to account for all of the airplanes in the air, culminating in the crash of flight 93 in a Pennsylvania field. We wondered what could possibly motivate someone to cause such horrific damage, to deliberately destroy so many innocent lives.Whitewashing the most peculiar institution:

a Lost CauseLeonard Pitts, one of my favorite columnists, just wrote about the persistent whitewashing of Confederate History in the old South, and pointed to the out and out lies that are being told about it. The biggest whopper, of course, is that the Civil War was not about slavery! Of course, the South was quite clear and unambiguous as to why they started a Civil War. In their own language justifying their secession from the Union, they described slavery as the primary reason for their treasonous behavior.

Here’s the Thing about equal rights

Herein lies a tale of history misunderstood, and then of history revived. It begins in Heidelberg, Germany in 1975. I was then a young soldier in the US Army, and with a fellow soldier, my friend Ted Withycombe, had taken a day trip to visit the storied university town of Heidelberg. While strolling along the Philosopher's Way, where students and professors had trod for hundreds of years, we chanced upon an unmanaged but well-trodden path that went up the hill towards the Heiligenberg, which other people were clambering up. There was no sign that described that path, nor could it be found on our map.

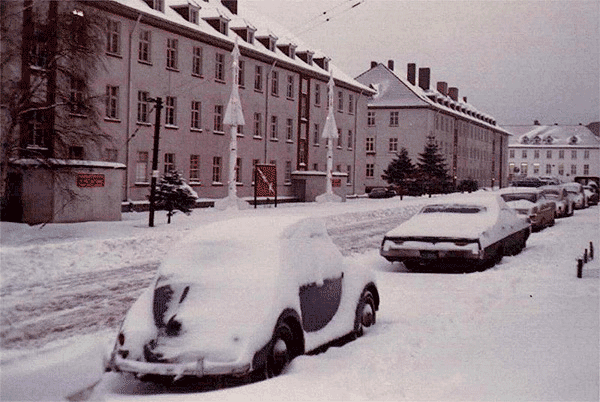

You can’t go home again . . . to Husterhöh Kaserne

Thomas Wolfe's famous suggestion, "You can't go home again" covers a large amount of territory; your home is not the only thing to which you cannot return to with any but perfect verisimilitude. Recently I became curious about my old neighborhood in Pirmasens, Germany, where I was stationed as a soldier in the U.S. Army during the mid-70's. Through the magic of Google Earth and the Internet, I explored the place I once lived, now thirty five years hence.Unforgettable, complete Holocaust story

If you were looking for just one story that would give you some sense of the personal impact of the Holocaust on its victims, survivors and their families, this is it. Spiegelman's cartoon version of his father's life before, during and after the Holocaust, of which he was a survivor, provides a more direct, complete and highly visual means of telling the story. Maus draws you close, and with each panel, you feel the emotional impact of this terribly difficult and sad world.

Storming the Bastille, then laundry

'Today we stormed the Bastille; I got there late; I heard it was bloody. Then I went home and had an argument with my mistress about the laundry. She spends too much time gossiping with the concierge. Hmmm, what's that I smell for dinner?'

Such parody is a little harsh, but it serves to underline the overall pedestrian nature of this historical novel; the author's subject deserved better. That subject is the French Revolution as seen through the eyes of three major characters: Desmoulins, Danton and Robespierre, two of whom were members of the decidely unsafe Committee for Public Safety, all three of whom were consumed via the guillotine in the most unsafe year of 1794.

Too pacific

I picked this book up on whim, to fill the hours of a long plane ride, mostly because of my admiration of the The Band of Brothers HBO series. I had read that the new HBO Spielberg-Hanks production The Pacific was also excellent, but I do not have access to HBO and was waiting for the series to be published in blue-ray. So I thought, the book The Band of Brothers by Stephen Ambrose, upon which the HBO series was based, was very good, so why not just read The Pacific in anticipation of that TV series?

Doc Holliday’s story

Robert's book Doc Holliday: The Life and Legend is a solid effort to document the life of one of the main participants of the shootout at the OK Corral, and provides a dramatic rendering of that famous event. I found it a nice diversion.

No matter how righteous a war, it's a terrible, sad and awful thing. Sometimes the reasons are defensible. But most of the time, they're not.

No matter how righteous a war, it's a terrible, sad and awful thing. Sometimes the reasons are defensible. But most of the time, they're not. READING

READING ARCHIVES

ARCHIVES CATEGORIES

CATEGORIES QUOTES

QUOTES